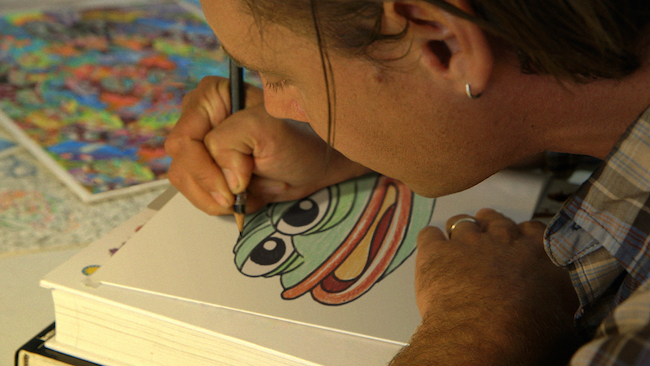

―I have read that “Feels Good Man” is your feature debut as a director. What did you guys do before this movie?

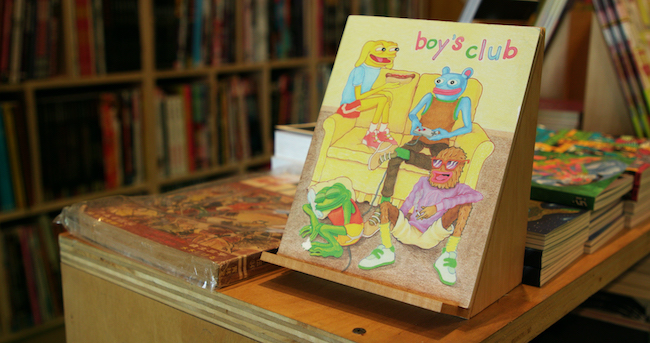

Arthur Jones: We both come to documentary as our second or maybe third career. I went to college as a painting major. I’ve always been involved in the arts, but painting, graphic design, animation. And then, I was helping friends make documentaries as a motion graphic artist and re-toucher. And Giorgio was making a documentary film about housing policy - he’s an architect by trade - and so we worked on that together. I did the animation in his film, and we started working on “Feels Good Man” together because that was such a good experience. But I love cartoons, they’ve always been my passion since I was a little kid. So “Feels Good Man” was an opportunity to really make a film about why cartoons are important. They are not disposable culture. They are a big part of the way we communicate. So that was something I was excited about.

Giorgio Angelini: I was playing music for most of my life, and I studied architecture really because of the housing crisis killed the music world, and I needed to find a new career. But I wanted to do film and I found the opportunity to make my first documentary about the history of racism and housing in America, and that’s how I met Arthur. And when we were finishing that, Arthur told me about his plans to make this film. I had known about Pepe for a long time because I spend a lot of time on Reddit. I knew Pepe as a meme and I was disturbed by its transformation. But I didn’t know Matt(Furie, the creator of Pepe) existent. Arthur had a personal relationship with Matt, so I was kind of horrified and embarrassed when Arthur was telling me Pepe’s back story. Anyway, so that’s sort of how it all came to be.

―So Did Matt ask for your help? Or did you want to help him by making this film?

AJ: I was friends with Matt and whenever I would see him at a party or something, I would often ask him about Pepe, and I could see that this story was beginning to take a little bit of a tall on him. And then we started talking about collaborating because I think Matt wanted to do something with Pepe that was positive. His first idea was working with me to help him make a cartoon that would explain what happened to Pepe. We talked to a few people in Los Angeles in entertainment industry about that. And you could realize that the negative baggage of Pepe was so bad that just no one wanted to talk to us. Some of them even thought that Matt was a neo-Nazi because he’s drawn the character.

―Oh no…

AJ: So after that experience, it occurred to me that a documentary was the best way to do it. And I just so happen to have been working on Giorgio’s film and a couple of other films with friends, and I think from working on those, I had the documentary bug. So I just asked Matt very straight forwardly, “I think you should let me make a documentary about it.” And he and I realized that the story with Pepe was unique enough that it should be captured and it should be captured by friends. So that’s the way it started.

―You can tell how much time has passed by watching Matt’s baby girl turning into a toddler. How long was the whole process?

GA: It was actually very quick for a documentary, partly because we really wanted to make sure that the film came out before the most recent presidential election. But it was about two years which for Ursula (Matt’s daughter) is half of her life [laughs.]

AJ: When all of the terrible stuff was happening with Pepe in 2015, that’s when Ursula was born. In other interviews we’ve done over the last year, people have maybe said Matt’s naive or asked why he didn’t do something sooner. The reality is Matt was a young father trying to provide for his family as an artist. So he was more concerned with changing diapers than fighting the alt-right in 2015.

―What was intriguing about this movie is that unlike a lot of documentaries where they just give you information on the topic, there is Matt at the center of it. As Pepe and Matt go deeper into trouble, the audience can also experience it in real time with them. Was it your intention to involve the audience by structuring the film this way?

GA: That was something that Arthur and I spoke about from the very beginning I think partly because we weren’t always documentary filmmakers. We came from different artistic backgrounds, and we felt like documentaries are often pieces of journalism first and film second. Like, we’ll just give you a bunch of information and educate you about something, and then it’ll end. But we wanted to really make it a film first and journalism second. Never compromising the journalism of it, but of course, recognizing first and foremost that we are making a film.

―I could see that.

GA: The other benefit we had in terms of your question about kind of learning along the way, is that the first half of the film, we are sort of telling a recent history. We were lucky because we were able to capture Matt in the middle of this legal fight, so we got to tell the story in real time. So that was a real gift and it really helped us create a very dynamic timeline.

AJ: And Matt’s legal fight, that was part of his personal journey. It’s a story of someone going from the passive to the proactive, and we thought that was a very powerful message for any audience member. For people who have problems in their lives, it’s a simple truth of dealing with that problem. And so we get to see Matt deal with his problems in real life, and we thought that would be powerful.

―You also used the actual footage of the depositions in the movie.

AJ: I think Matt’s deposition is a powerful moment for him, because you see that his energy and optimism and sweetness shine through even in an uncomfortable moment. And I think that we made this film for a youth culture audience. Most documentaries are maybe watched by slightly older crowd. But I think if I had seen Matt in this uncomfortable situation as a young person, it’d be inspiring. It means that he’s living his life as an artist, he’s living it without compromise, he’s standing up and doing what’s right, but he’s still being himself. That was a moment in the film where I feel so proud of Matt. And I hope that the audience feels the same way.

―How did you get the 4channers, Pizza and Mills, on the film? You even filmed at Mills’ home. Aren’t they supposed to be anonymous?

AJ: Mills, well, Pizza too, their faces are on 4chan. And people seeking attention is kind of looked down upon within 4chan culture. Mills had some videos that I found online, and there is that video of him lying in bed and he’s holding his phone up like this, and he says “What does Pepe mean to me?” And that was the video I found so intimate and striking. I remember that the first time I watched it, he’s making eye contact with the camera but I felt like he was making eye contact with me. And I just had a feeling he was going to be in the film. It took a little Internet sleuthing to find his contact information, but this whole film was Internet sleuthing [laughs.] It was a lot of deep dark Internet research to get this thing made and that was part of it.

GA: But the other part of that too is that, it’s just the nature of the Internet now that even people on 4chan like Mills are trying to build careers as online personalities. And so in some way he’s seeking popularity by exploiting himself on 4chan and being the center of jokes and embarrassment. It’s a very twisted and strange life that a lot of, especially Americans are going through now where they feel like they have to monetize every aspect of their life and put it online and livestream it, and captured in a meme and put it on TikTok with the hope that you will go viral and be able to build a career out of that. It’s a very strange world.

―You also have a scholar, psychologist and journalist providing additional context. And even an occultist!

GA: [Laughs] He was referred to us by someone who had listened to an interview randomly of me and I had just said that I was working on this new project about Pepe. And then this guy emailed us and said, “Oh, if you’re doing a project about Pepe, you should check out this guy, John Michael Greer.” And so Arthur and I googled him, and the first images you see when you google him is this long huge beard and robe. And he’s what’s called an archdruid, like people basically worship kind of ancient pagan Scandinavian British… I don’t even really understand what druid is [laughs.] It has something to do with Stonehenge in England.

―[Laughs]

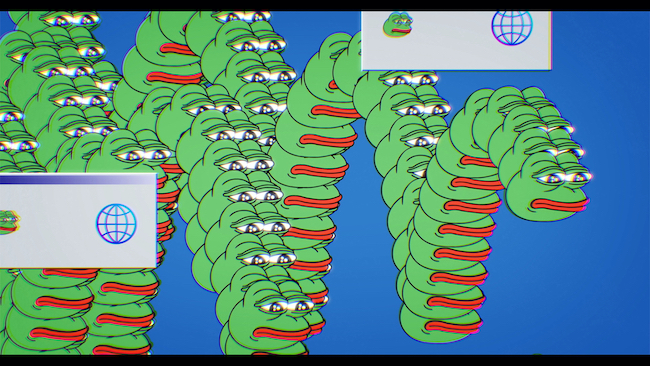

GA: But we started reading his work, and he’d written very intelligently about something very central to our film that is very hard to explain which is the social power of the memes or meme magic. And we knew that we always wanted to talk about meme magic, and like everything else in our film, it’s both absurd but also very serious. And he seemed to capture that entire quality in one person. So we are super lucky that we got him because I feel like he explained meme magic in a way that a journalist or any other expert really couldn’t. And as filmmakers, I think we’re also testing the audience to say like, “Are you going to believe this guy or are we joking?” It was one of the more fun moments of making the film for sure [laughs.]

―What about the guy with cryptocurrency?

GA: We wanted to capture how far gone the whole thing with Pepe had gotten, and Pepe cash seemed like the most absurd example. But we also filmed with the woman in Russia who makes giant paintings replicas of famous artworks and she puts Pepe in place of the actual subjects [laughs.] So there was a lot of crazy stuff happening around the world.

―Why do you think Pepe became the symbol for hope in Hong Kong? Did people in Hong Kong know that Pepe is known as a hate symbol in America?

AJ: Pepe has different connotations in different places all over the world. Pepe had been popular in Korea and Taiwan and Hong Kong and China while it was being used as a racist symbol in the United States. The sad frog is basically a symbol for an unhappy person on the Internet. But the Hong Kong thing specifically happened because there was a protester who was shot in the face with a non-lethal round by the Chinese police. And she showed up to the next protest with the bandage on her eye, a hard hat on, and she made a handmade sign and it’s a drawing of Pepe but it’s her. He had a bandage over his eye. And that image got picked up by the Western media, that ended up being put on Western websites, published in Western newspapers, and they realized, “Oh, people are watching this. They find this to be a newsworthy thing.” So Pepe became a symbol for “Help us.”

―I see.

AJ: It’s also important to note that Pepe is a symbol for anonymity as well, because the Chinese authority is using facial recognition shot software to track protesters so they are wearing masks. So Pepe was a way of standing in for the every man again. And it also speaks to how important memes are to politics and organizing all over the world right now. It’s not just in America that memes are important, it’s all over the world. So once again, it’s the surprising use of memes that affects culture in the way that’s like lightning-fast and unexpected.

―It must have been a surprise for you guys. Did it happen at the end of the filming?

GA: We were all shocked and surprised and elated and happy about it. It was a really moving experience. This happened three weeks before we had to submit the film to Sundance. We were lucky because one of the people we interviewed for the film, this journalist named Aaron Sankin, happened to move to Hong Kong just two weeks before. So we connected him with a photojournalist in Hong Kong named Diana Chan and they went and shot this for us. Arthur made some shot list of the kinds of things we want to see. And the next morning we woke up to a google drive filled with all this footage and we literally cried, because it was so beautiful.

―In the film, Matt’s friend tells him that this could only happen to him. But as you watch the film, it made me realize that this could happen to anyone at any time. So this film really made me think and made me scared as well. What do you think was the biggest thing you got through making this film?

GA: I would be curious to hear Japanese perspective, but at least in the Western world, the way that the Internet seems to be configured currently, it tends to make us more combative, angrier, more cynical. And I think we wanted to make the film remind people that’s a choice and that we shouldn’t feel ashamed to be thoughtful or loving or empathetic, just because you are on the Internet and just because that isn’t cool to be like that online. These things are influencing real life now. We have to take much more seriously the way that the Internet influences us as people because it spills out into everyday life.

AJ: I agree with the things that Giorgio said. I think the things that I take away from this film are highly personal. They are the attachments to I have to the people who made the film with us. And that in itself I think says something that’s similar to Giorgio’s take on this. Making this film was full of surprises. There were so many times that we were surprised by Matt or something that happened. And one of those nice surprises is that when you create a piece of art with a group of talented, smart, committed people, you are always going to be shocked and amazed by how lovely those people are. Even right now, talking to you in Japan, what a wild experience this has been. So just leaving yourself open to surprise and committing yourself to creativity are maybe simple truths, but they are the things that I think about when thinking about “Feels Good Man.”

text Nao Machida